The Rise and Fall of Tupperware

The business model that made Tupperware a success ended up making it a failure.

Last week, Tupperware announced that it was closing down in South Africa a few months after declaring bankruptcy in the United States.

How did such a well-known brand end up failing?

The short answer is that the business model that made Tupperware a success ended up making it a failure.

Here's the cautionary tale of Tupperware's rise and fall that all business leaders and entrepreneurs must know.

Earl Tupper started Tupperware in 1946, and in its early days, Tupperware was sold in hardware and department stores.

However, despite a lot of investment, the business struggled until a single mother from Detroit changed everything.

Brownie Wise had come across Tupperware in a hardware store and, after trying the products, saw the potential.

Brownie had experience with marketing, advertising, and a new sales model of home-based sales demonstrations, which she thought could work for Tupperware.

She approached Earl for permission to sell Tupperware, and he agreed.

She then created one of the business model innovations that would be at the centre of Tupperware for decades to come — the Tupperware parties.

In Tupperware Parties, a host was paired with a Tupperware dealer who presented the products to guests.

The parties were fun and interactive and perfect for the time. Many women during the post-war period were focused on homemaking but also looked for opportunities to supplement income and socialise.

Tupperware parties provided all of the above and were a very effective sales model.

This model was so successful that Earl Tupper removed all the products from the stores, hired Brownie Wise, and invested heavily in this new business model.

Tupperware sold, marketed, and distributed its products primarily through individuals who leveraged personal connections and product demonstrations.

Over the next 50 years, the company continued to be successful using this model and was even named one of the world's most admired companies by 2008.

However, the business model that had been so successful in the past started to fail as consumer behaviour changed.

The rise of e-commerce not only resulted in the loss of market share but also a shift in consumer habits.

People now valued convenience and speed.

However, with Tupperware, up until October 2019, if you wanted to buy a product, you had to find an independent sales rep or attend a Tupperware party.

Tupperware was so behind in changing its business model that the Tupperware Store on Amazon was only opened in 2022.

By the time Tupperware attempted these changes, it was already too late.

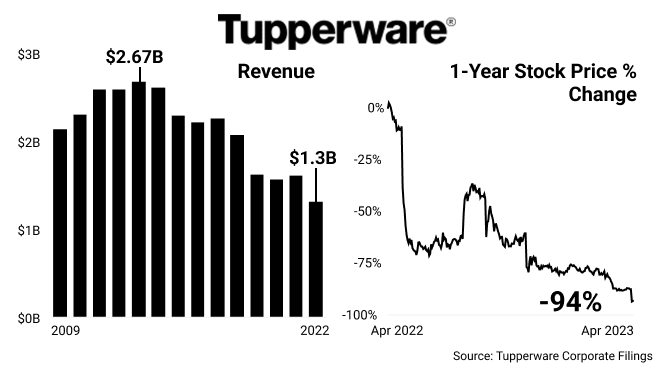

In a way, Tupperware arrived late to its own party, and the revenue decline below tells that story.

Why did Tupperware not change things earlier?

When you look at the 2016 annual reports, specifically the CEO's letter to shareholders, it seems the company always assumed the current business model worked but just needed to be "strengthened” despite years of falling sales.

A key lesson from this is understanding that some things don't need fixing; they need to be broken apart and drastically changed.

If something isn't working, examine your business closely and be ready to make bold decisions.

Sometimes, it needs an adjustment, but other times, it needs an overhaul.

This reminds me of the Elon Musk quote below. Smart people try to improve things that shouldn't be there in the first place.

The other key lesson is that you can have a fantastic brand, but you will struggle if your distribution is ineffective.

Tupperware has always had a strong brand. Some estimates say that in the 1990s, 90% of American homes had at least one Tupperware product. Everyone knew about Tupperware, but no one knew a store where you could buy it.

Compare this with Coca-Cola. Its superpower is not only the brand but also the distribution. You can go anywhere in the world and order a Coke.

So what now for Tupperware? The business has been sold globally, and the new owners will try to turn it around by shifting to a "digital-first, technology-led and asset-light" business model.

For South Africa, however, the news is more unfortunate.

Tupperware South Africa is not included in the deal to be bought with the other global operations. As a result, it will not receive any licensing or support and will need to shut down.

Where’s the Money, What’s the Move?

The exit of Tupperware from South Africa may be an opportunity for a local brand to enter the market. South Africa has demonstrated a demand for fresh local brands.

Examples are Fieldbar, with its category-defining luxury cooler box, and Bathu, which has done exceptionally well in footwear.

Both brands have built huge following in a short space of time. Bathu was founded in 2015 by a former PWC accountant, Theo Boloyi, in a local township (Alexandra). It now has over 30 stores in South Africa.

Fieldbar was founded in 2018 by Lee Hartman and Corban Warrington. Feildbar products were so popular that they often sold out for months.

With Tupperware's exit, there will no longer be a category-leading brand in South Africa. Could another brand not capture the kitchen and food storage space? The market seems large enough, and consumers in South Africa seem willing to pay for well-designed local brands.

Thanks for reading! What do you think?

Tupperware became to compliance’s reading your article l can say the model was great as the meet ups were great then had it adopted to the online footprint am sure it would have remained in the game like Nokia and blackberry we can only learn and grow these need of continues growth and development