Why Shoprite Quit Ghana After 20 Years

Not every market deserves your time. Walking away can be the smartest move.

Recently, Shoprite announced that it is exiting Ghana—bringing the total number of African markets Shoprite has left to seven.

Is Africa’s largest retailer tired of Africa? And what’s the big lesson every business leader should take away?

Shoprite’s Ghana Entry

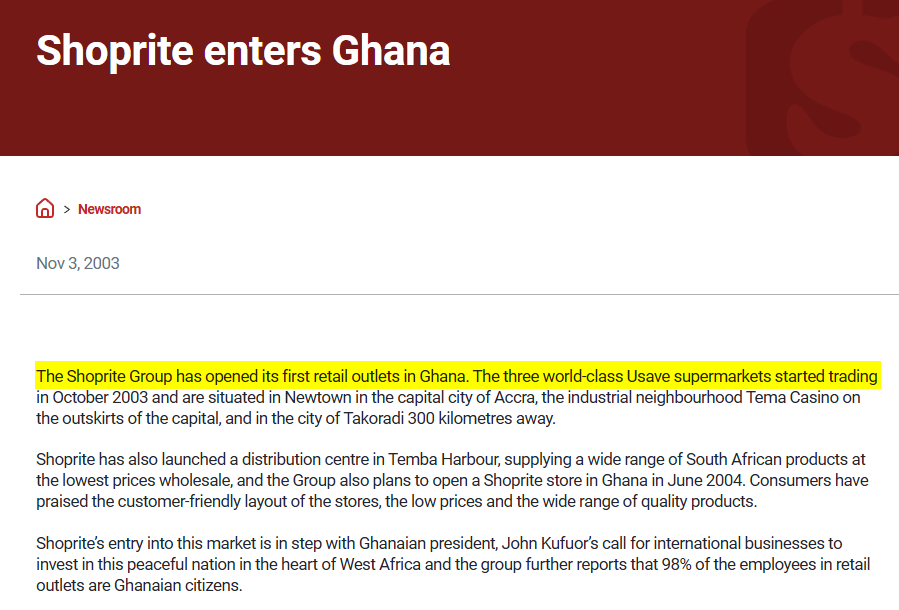

Shoprite entered Ghana in 2003, armed with strong ambitions for growth. At the time, Ghana’s economy faced challenges, but the general mood was one of optimism.

That same year, Ghana became one of the first African countries to receive an internationally recognised credit rating. As Reuters reported:

“In 2003, S&P gave it (Ghana) a B+ with a stable outlook. That’s four rungs below investment grade, but given the nation’s bright prospects at the time, its leaders were enthusiastic. ‘To ask if Africa is ready for portfolio investment is to ask a starving man if he is ready for food,’ Ghana’s finance minister said at a UNDP event in New York.”

This favorable climate coincided with Shoprite’s broader Africa strategy, which began in the 1990s. The company expanded into Namibia, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, and several other markets. In 2003, Shoprite entered Ghana with three Usave supermarkets.

Despite the initial promise, the business never gained traction.

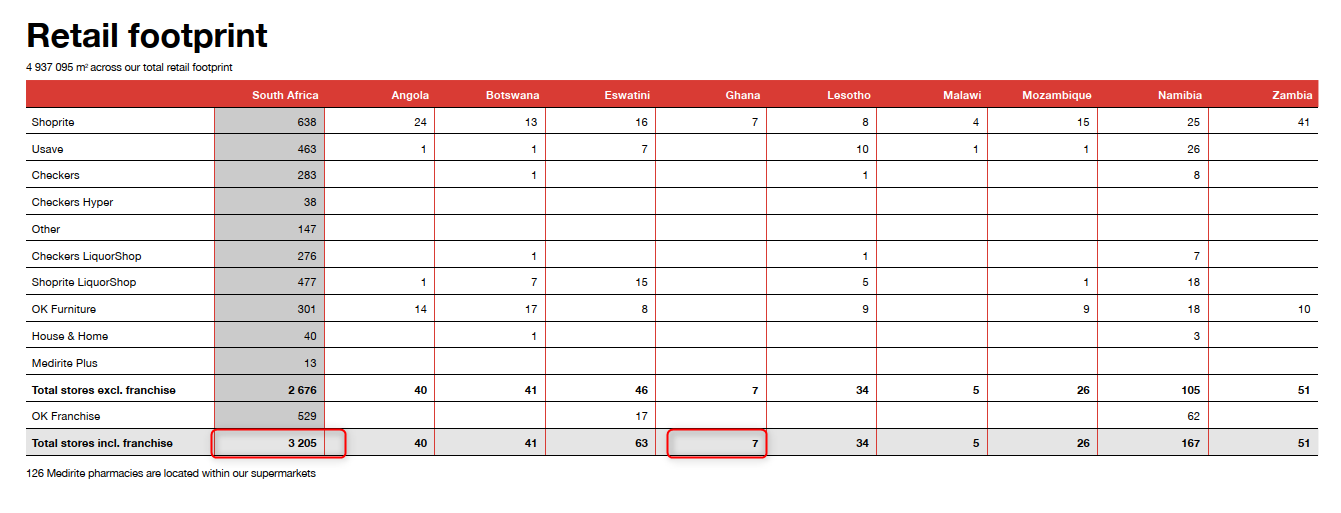

A decade later, Shoprite had only increased its footprint from three to four stores. The stall in expansion was partly due to Ghana’s volatile operating environment and Shoprite’s struggles to capture meaningful market share.

Why Exit Now

The idea behind Shoprite’s African expansion was growth. This made sense. South Africa’s GDP growth was expected to be much lower than the rest of Africa, which is ultimately what happened.

Over the past decade, South Africa’s GDP growth has averaged only 0.7%, compared to Ghana, which grew above 5%.

But for Shoprite, that growth never really came. It was the exact opposite. While Shoprite added over two thousand stores in South Africa since 2003, Shoprite Ghana had only added four stores in over twenty years.

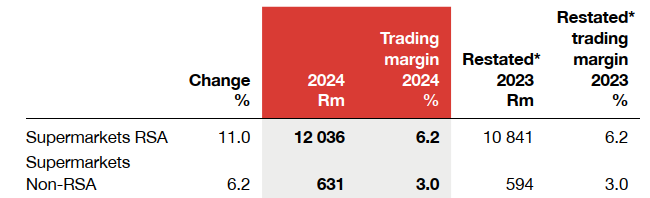

This trend has become even more pronounced recently. In the FY24 financial year, the South African supermarkets business grew around 11%, about double that of its non-South African operations. Ghana specifically delivered just 0.3% growth in rand terms.

In addition, the South African Supermarkets were twice as profitable as the non-South African ones.

To further compound matters, Ghana’s risk premium (the higher expected return to compensate for a country's risk) is about 12%, while South Africa’s is about 4%. In other words, Shoprite was taking on much more risk for a lot less return.

Capital Allocation

Given this performance gap, it’s logical that Shoprite would withdraw from Ghana and other underperforming markets. This marks the seventh exit from an African country in the past four years.

Does this mean Shoprite will miss out on future growth? Possibly. But a good strategy is about saying no to “good” opportunities so you can pursue the best opportunities.

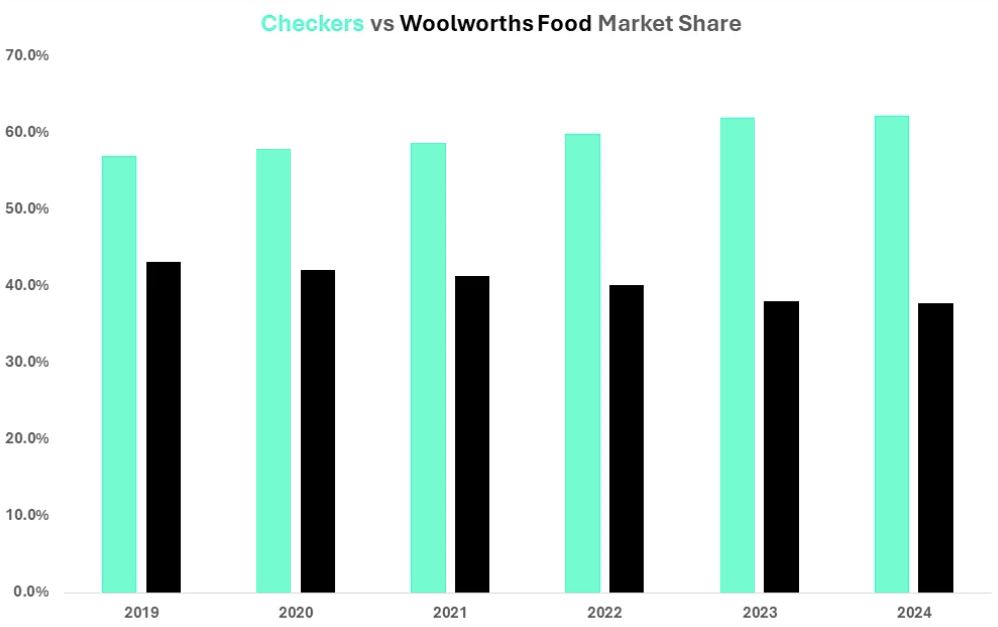

Currently, South Africa presents a really strong opportunity for Shoprite, driven by the massive success of Checkers Sixty60, the one-hour grocery delivery service. In recent years, Shoprite has not only taken market share from the struggling Pick n Pay but also from the popular Woolworths Food.

The effort, attention, and bandwidth consumed by small, low-return markets like Ghana doesn’t seem worth it.

But there is also a big lesson for every business leader, even if you only operate in one country.

Where’s the Money? What’s the Move?

Even a business in one country has different segments, such as cities or customer groups. To continue to stay ahead, one needs to evaluate which segments to invest in continuously because that can often make the most significant difference in terms of how successful you are.

Incorrectly allocating time, attention, and capital to opportunities and markets that offer poor returns can be a fatal mistake.

When Steve Jobs returned to a struggling Apple in 1997 that was on the verge of bankruptcy, he found the product line up bloated to satisfy multiple retailers.

He famously cut it by 70%, leaving Apple with just four core products—a decision that paved the way for one of the greatest corporate comebacks in history.

Often, the best moves to make money are about doing less and improving focus, even if sometimes “you need to fire your customers”.

Not every market deserves your time. Not every client deserves your service. Walking away can be the most profitable move you make.

So ask yourself: What do you need to cut? And where should you reallocate those freed resources to unlock real growth?

Why do you think?